For every Spitfire and Hurricane, dozens of British fighter aircraft remain hidden in the shadows, neglected by popular history.

Some of these were brilliant, some were terrible, and some were just unlucky. Of course, forgotten is a subjective term, and you may know some or even all of them. They are all fascinating designs that cast light on the whole dramatic story of the British fighter plane:

10: Bristol M.1 Monoplane Scout

This excellent, exceptionally clean, monoplane fighter had its chance to fight curtailed by an overly cautious War Office, spooked by some pre-war crashes involving monoplanes. Monoplanes were banned, and even after the German Eindecker scout series had proved the effectiveness of the monoplane in 1915, it was still a struggle for the concept to gain acceptance.

This didn't deter Frank Barnwell, a Scottish aeronautical engineer, from persisting with the M.1 monoplane. Heavy losses on the Western Front lent urgency to the development of an aircraft of superior performance. The M.1 proved capable, but the War Office was nervous of its high landing speed of 49 mph and monoplane configuration.

10: Bristol M.1 Monoplane Scout

Royal Flying Corps pilots on the Western Front were impatient to receive the new aircraft, but things progressed more slowly than expected. Rumours abounded that another reason for its protracted delivery was an embarrassing crash by a senior officer of one of the prototypes, relating to the high landing speed.

Only 125 aircraft were built and were relegated to training roles in England, as well as service in Palestine and the Balkans. No. 14 and No. 111 Squadrons based at Deir-el-Belah, Palestine, flew the aircraft from 1917. It survived a brief time in the new Royal Air Force before being retired in 1919.

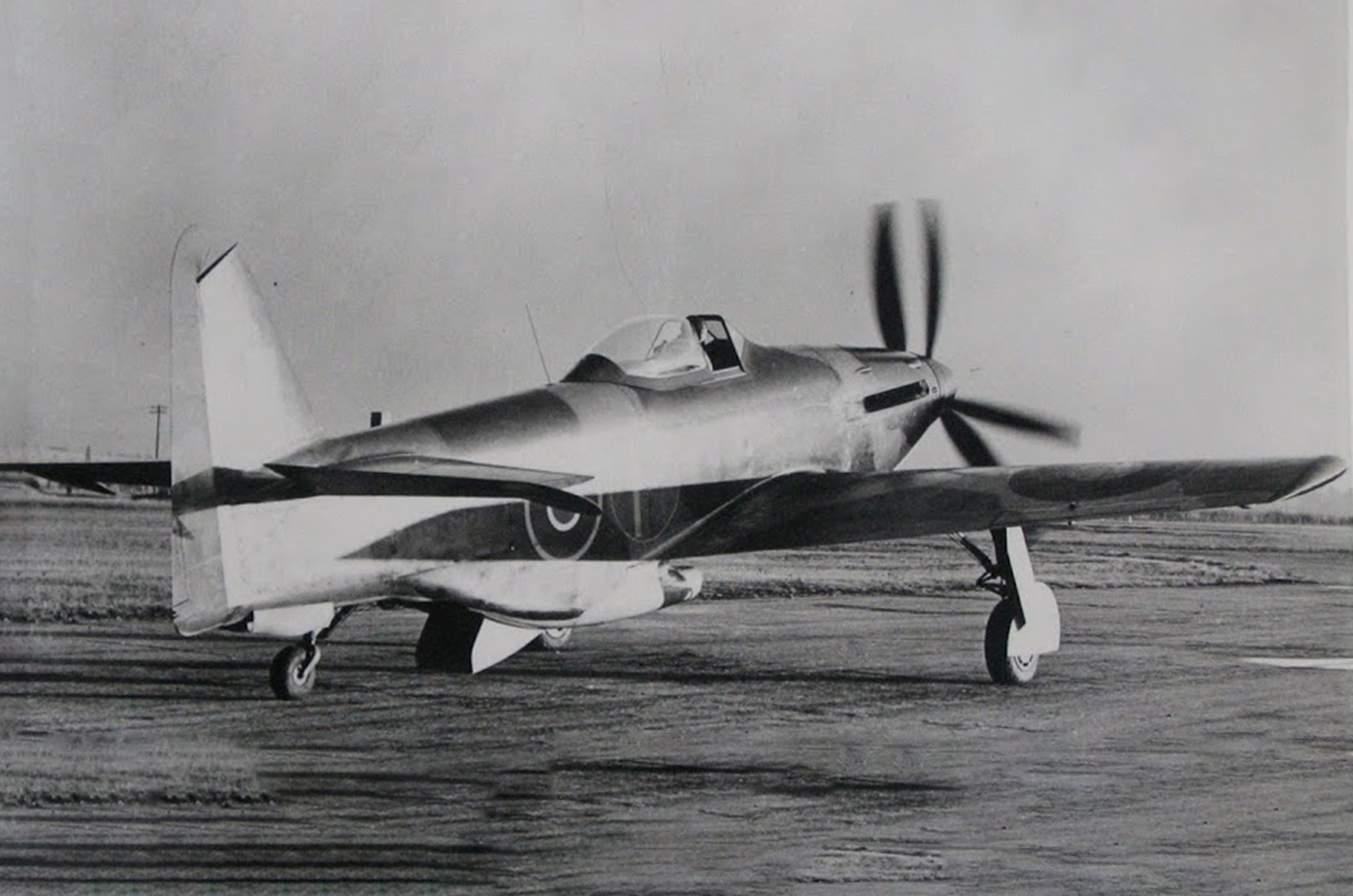

9: Westland Whirlwind

In many ways an advanced and ingenious design, the sleek twin-engine Westland Whirlwind was one of the fastest and best-armed fighters of its generation. Powered by two Rolls-Royce Peregrine engines and armed with four nose-mounted 20-mm cannon, this compact fighter first flew in 1938.

The extremely capable ‘Teddy’ Petter designed the Whirlwind. However, the project was seemingly cursed. Early technical issues arose with the proposed Oerlikon guns, as well as with the replacement weapons, the 20-mm Hispano, which necessitated a redesign of the Whirlwind, and problems with engine deliveries.

9: Westland Whirlwind

As a light fighter-bomber armed with 250- or 500-lb bombs, the Whirlwind was effective, proving itself in sweeps of the Channel coast and France. Despite the design's great promise, only 114 were built, and it was withdrawn from service in 1943.

There were several reasons the Whirlwind was not built in greater numbers. One reason was the discontinuation of its power plant, which led to a general concentration of effort and resources on the Merlin. Another reason was the availability of more manoeuvrable, easier-to-maintain single-engine fighters. The fact that the aircraft was too small to be easily converted into a radar-equipped two-seat night fighter also counted against this potentially world-beating fighter.

8: Sopwith Dragon

Add your comment