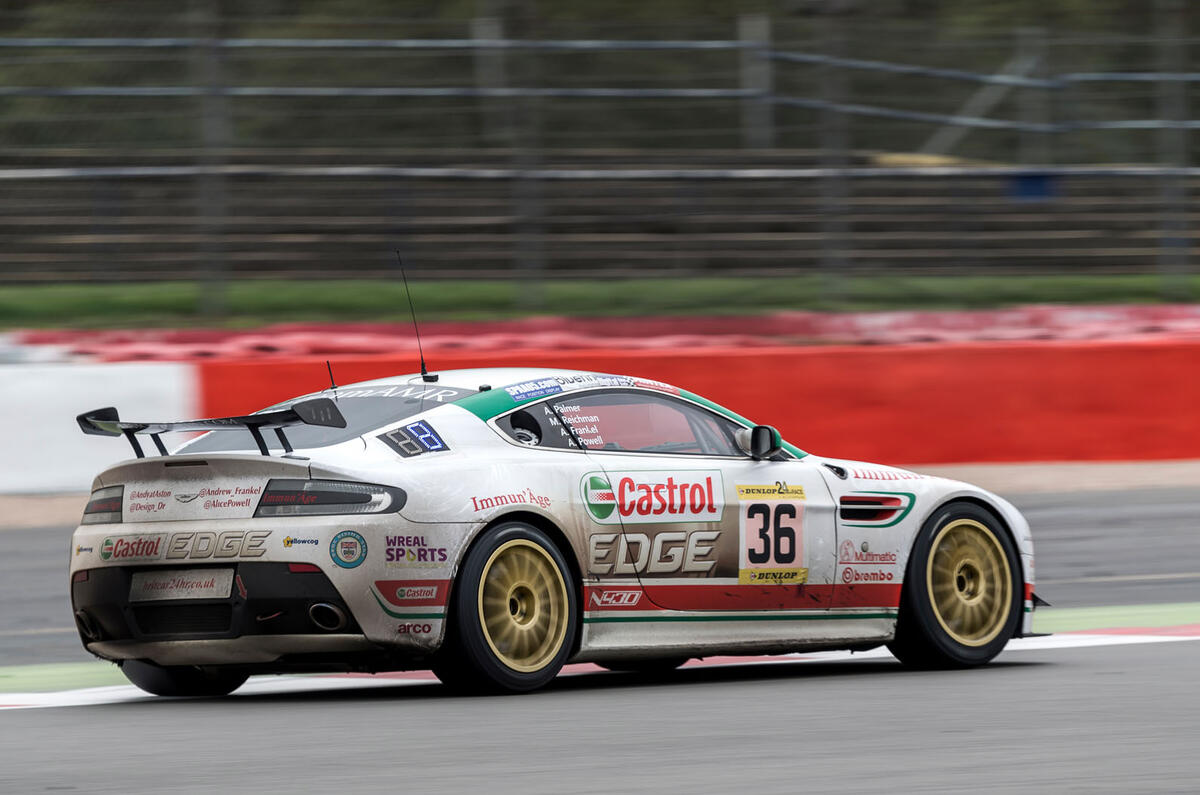

There are a lot of things to think about when you’re flying backwards off a race track at over 100mph. Where’s the car going to go, what’s it going to hit and is it going to hurt are just three.

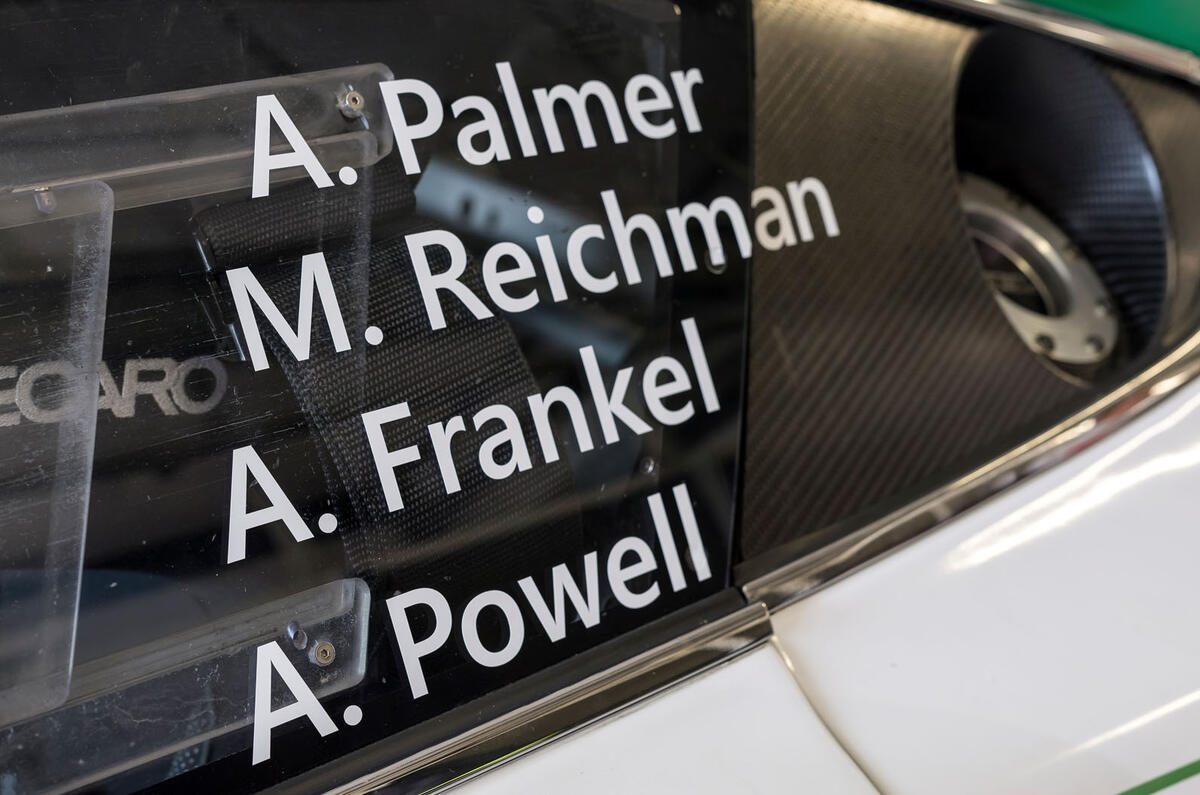

For me, however, far more difficult than any of that was what I was going to say to my co-drivers, the team of Aston Martin’s own Special Projects vehicle engineers and all the support staff who’d given up their weekends at home for two days without sleep at a cold, blustery and often extraordinarily wet Silverstone. Sixteen hours into a 24-hour race, I was about to ruin it for all of them.

Ostensibly, we were there as part of on-the-job training for Aston Martin’s new boss, Andy Palmer. An engineer who started his career designing gearboxes for Rover before rising to become responsible for the global output of Nissan, he wanted to ensure that when he spoke about racing being part of Aston Martin, he’d know what he was talking about.

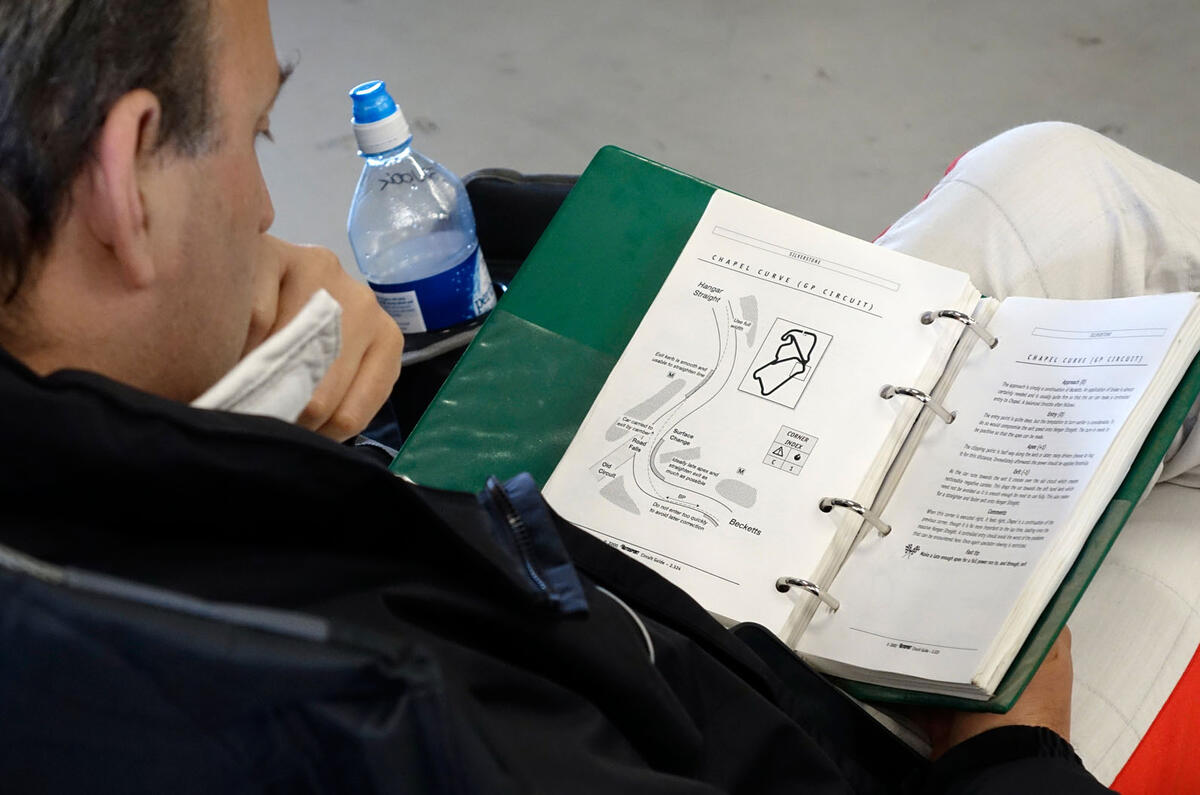

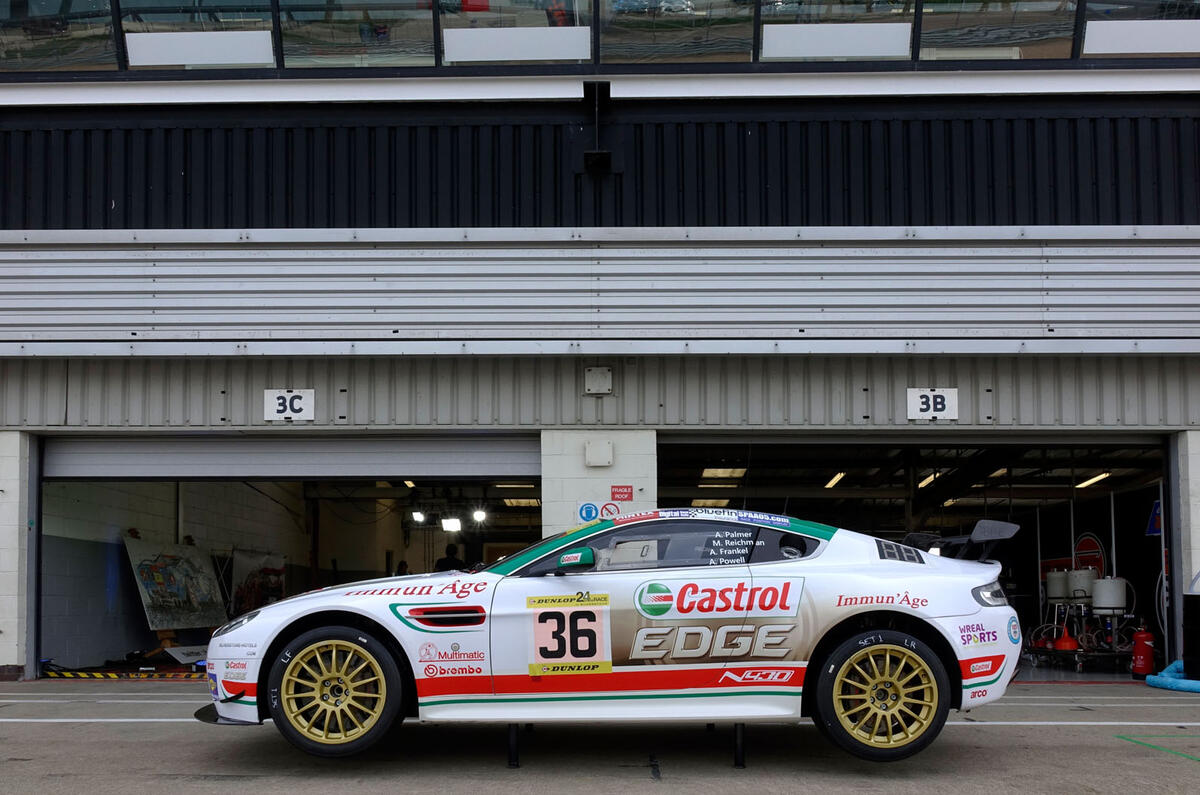

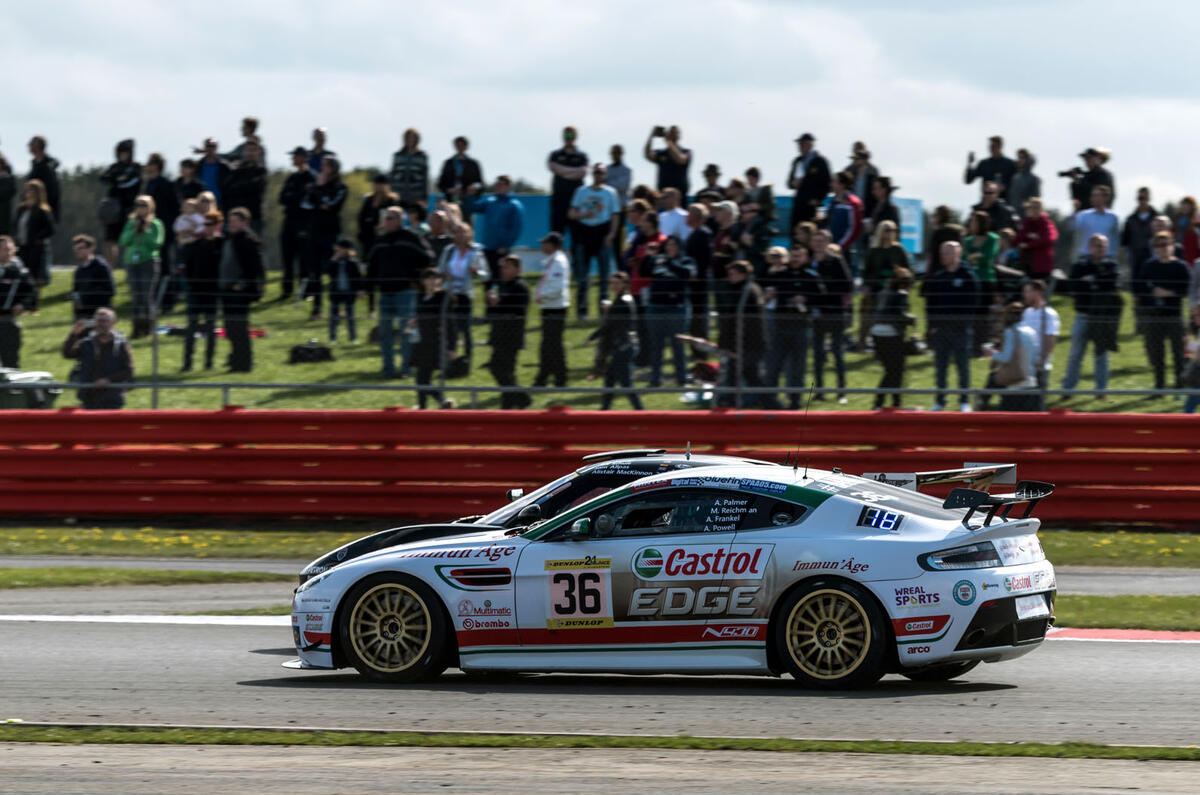

Another CEO might just have visited the team and a few events, but Palmer practises what he preaches. So despite having completed only enough races to lose his rookie sticker, and none in anything remotely as powerful as a 430bhp Aston Martin Vantage GT4, he duly reported to Silverstone for what would turn out to be 24 fairly extraordinary hours of racing.

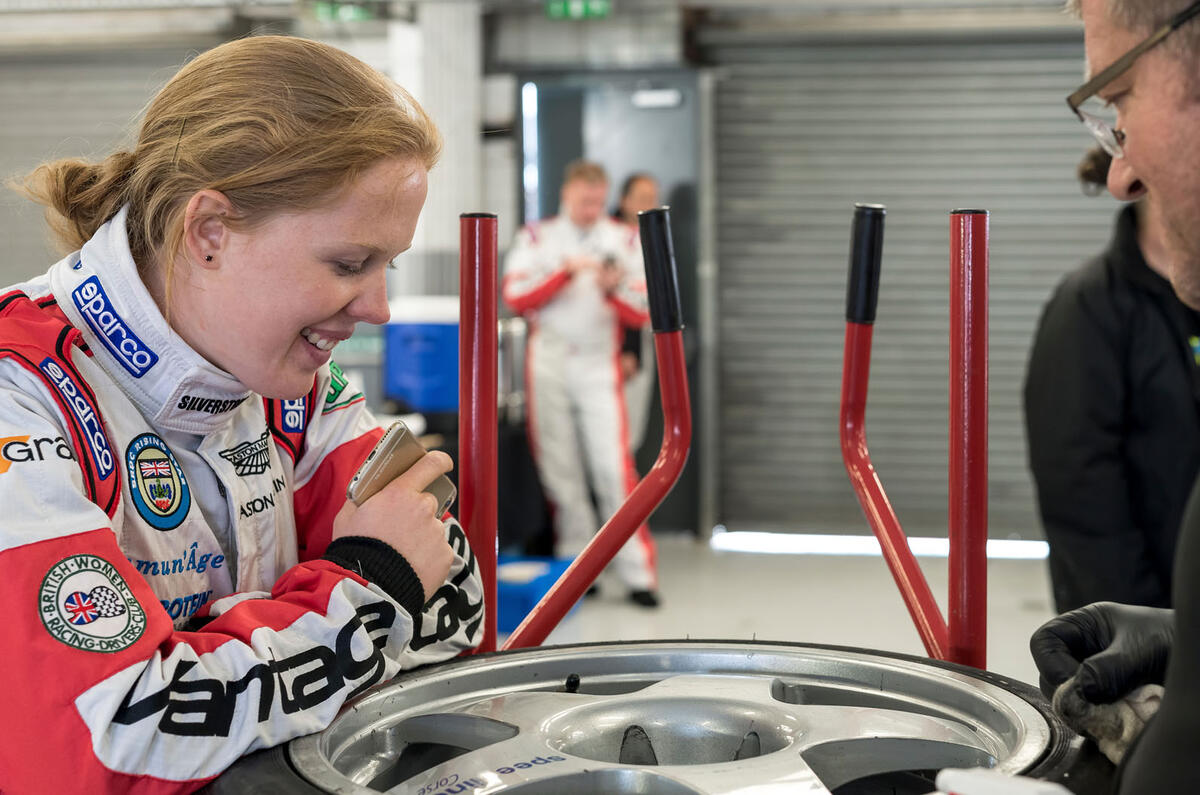

With him was his creative director, Marek Reichman, who has done a fair bit of Aston racing between Aston designing, and Alice Powell, the current Asian Formula Renault champion, the only woman to have scored points in GP3 and a multiple winner in Formula 3. And me, the bloke there to tell the tale and, as the only one to have done long-distance racing, not crash the car.

In testing, Alice was quickest, with Andy slowest. Alice then qualified the car 18th out of 30 on the grid behind two other Astons whose times not even Alice in max attack mode on fresh slicks and a thimbleful of fuel could get near.

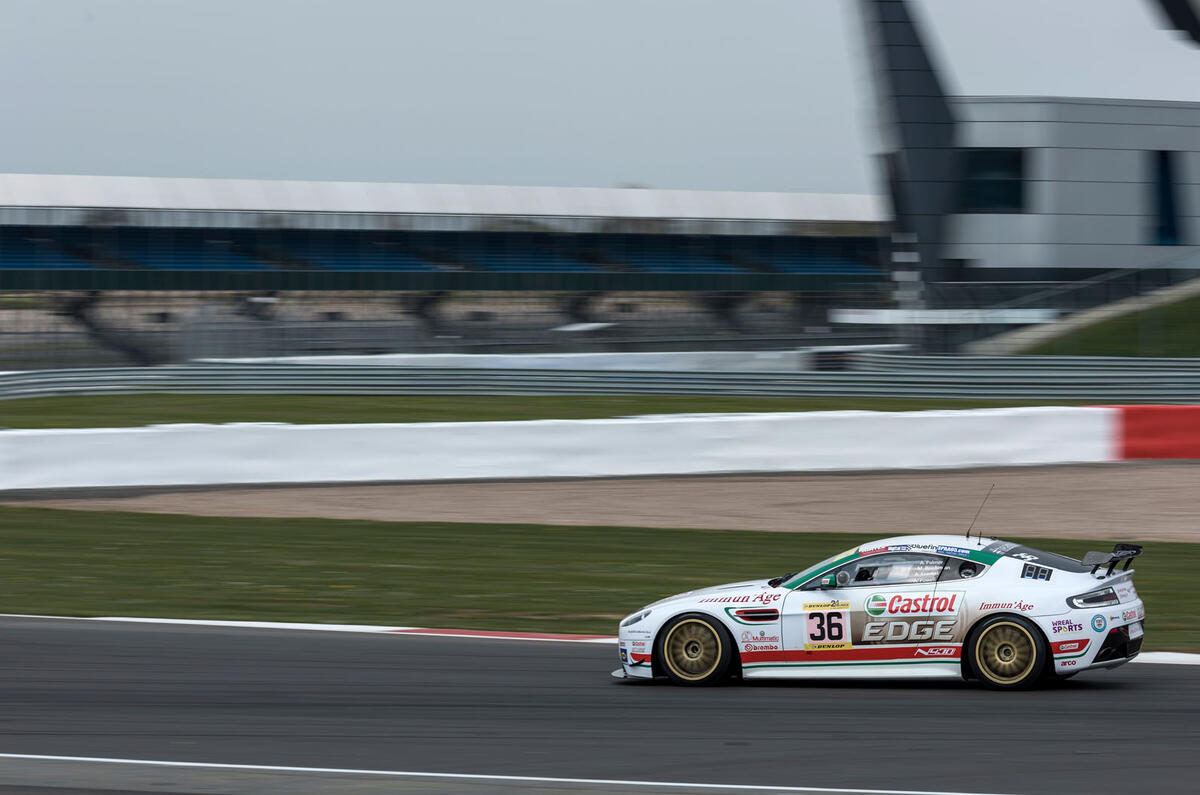

Then again, James (all factory Aston race cars have a name) is an old soldier – a 2007 chassis brought up to date but kept with standard bodywork and its 4.7-litre V8 in street specification. And I’ve done this race enough times to know to wait for it to come to you; there is always attrition through accident and unreliability and if you can weave your way past that twin-headed monster, a decent result awaits.

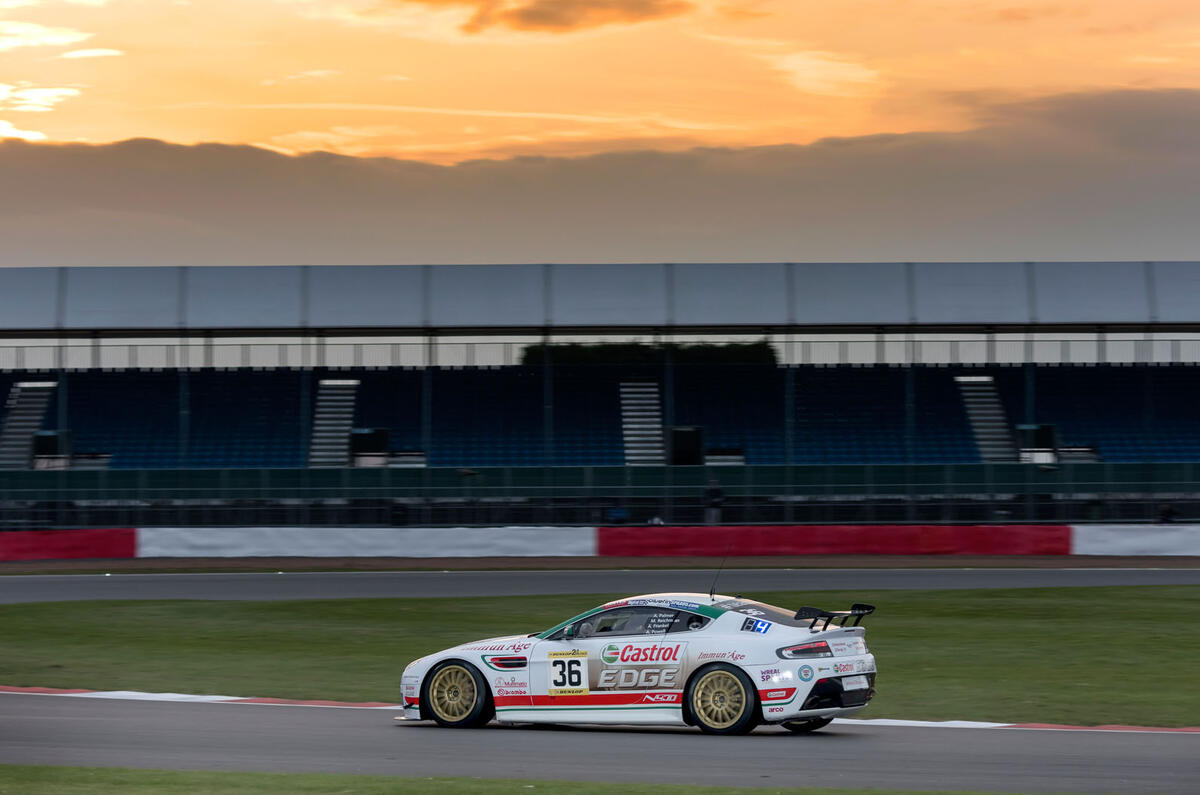

The idea was that Alice would start the race at 4pm on Saturday, cycling through Marek and me so that when Andy got in the car, he’d drive into the dusk, thereby ensuring a progressive introduction to night racing for our least experienced driver.

Except it didn’t happen that way. Alice went fast, as did Marek until the tyres started to wilt, which meant that I got fresh slicks and one of the happiest hours I can remember in a racing car. Driving as much for economy as lap time – lifting between gearchanges and short-shifting – I could barely believe the times James was doing.

Then Andy got in, a driver unrecognisable from the one seen testing two days earlier. He was quick from the out and just got quicker; soon he was right on the pace of his team-mates.

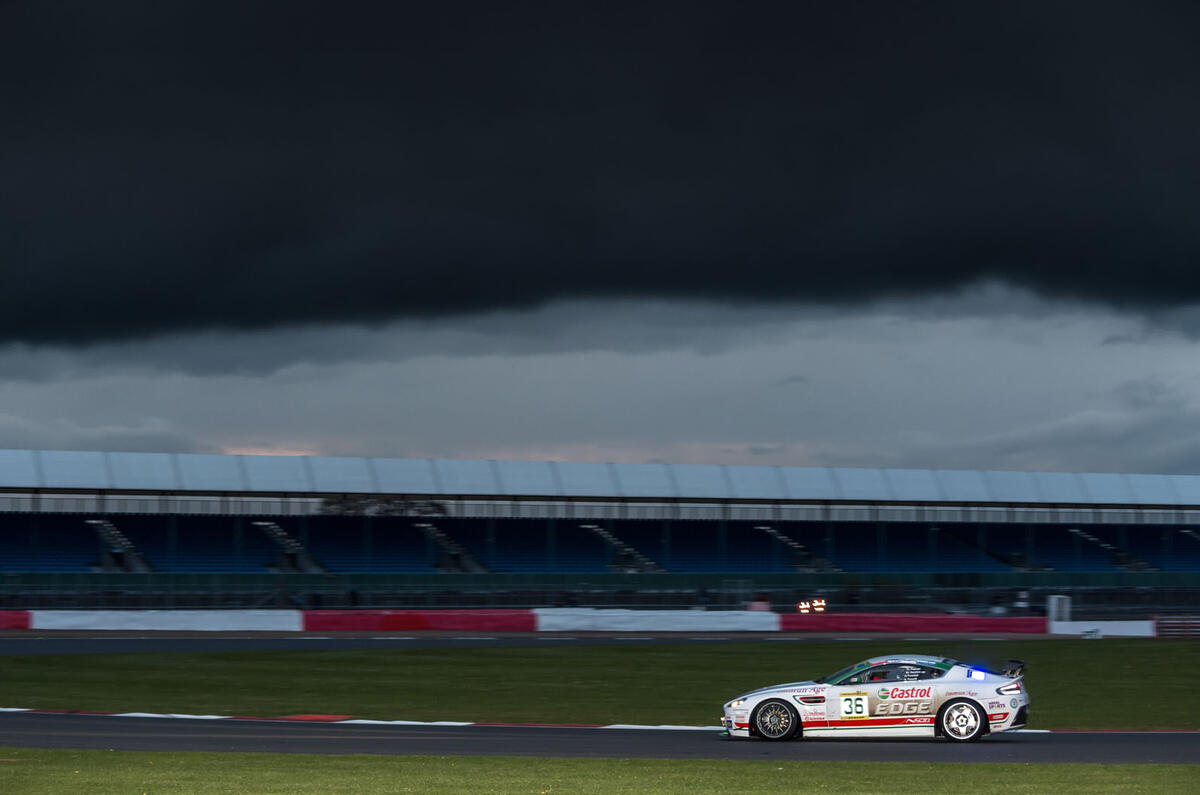

But darkness and the weather arrived arm in arm, rain of a kind I’ve not seen at a British track. As Andy slithered to a halt for wet tyres and hopped out, our professional driver was ready to take over.

Join the debate

Add your comment

After the racing.................