Grand prix racing isn’t supposed to produce certainties. The laws that govern this most sophisticated of sports are framed to promote such variability in driver-team-powerplant-chassis combinations that predictability is a small risk.

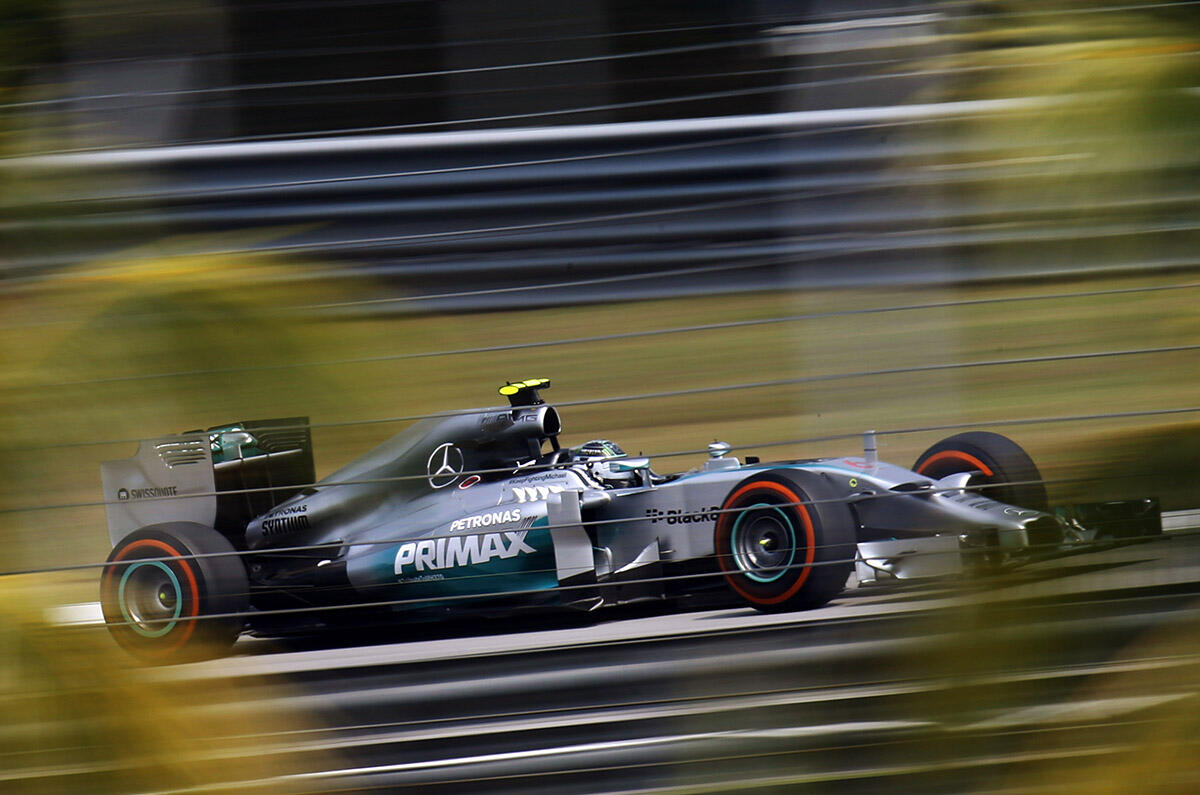

Yet this year, it hasn’t worked. Those who predicted serial wins for Mercedes’ powerplants have been right seven times out of eight, and even the recent Canadian win for Red Bull’s (Renault-powered) Daniel Ricciardo was achieved because one Mercedes driver’s brakes failed and the other’s engine had an unprecedented power loss.

Powerplant performance has been this year’s big differentiator. The availability of Mercedes power is the reason why previously underachieving Williams made life so hard for Ferrari and Red Bull last time out. Under such circumstances, who’d bet against another Merc-powered victory this weekend in Britain?

At Brixworth, 20 miles north of Silverstone, where Mercedes race engines have been created since 1993, such thoughts are heresy. The 400 inmates of HPP (for High Performance Powertrains) don’t think such things, let alone voice them. Past wins are good, but future success is the issue, and it must be earned.

So says Andy Cowell, the calm-voiced, white-shirted head of engine development at Brixworth who meets us in the foyer of his well ordered complex, surrounded by wide lawns and reeking of superior organisation. Cowell’s main job is to produce five powerplants for each of this season’s Mercedes-powered F1 drivers: two each from Mercedes, McLaren, Williams and Force India. That’s 40 powerplants, plus spares and repairs.

For Cowell & Co, glib assumptions are for other people. “This is a high-risk business,” he asserts. “You can test, but you won’t know where you stand until you go racing. Even when things are mostly going well, all you can see are your weaknesses. At the first race in Melbourne, the negatives associated with Lewis’s retirement were greater than the positives of Nico’s win – and that’s how it should be. Overconfidence always lands you in trouble.”

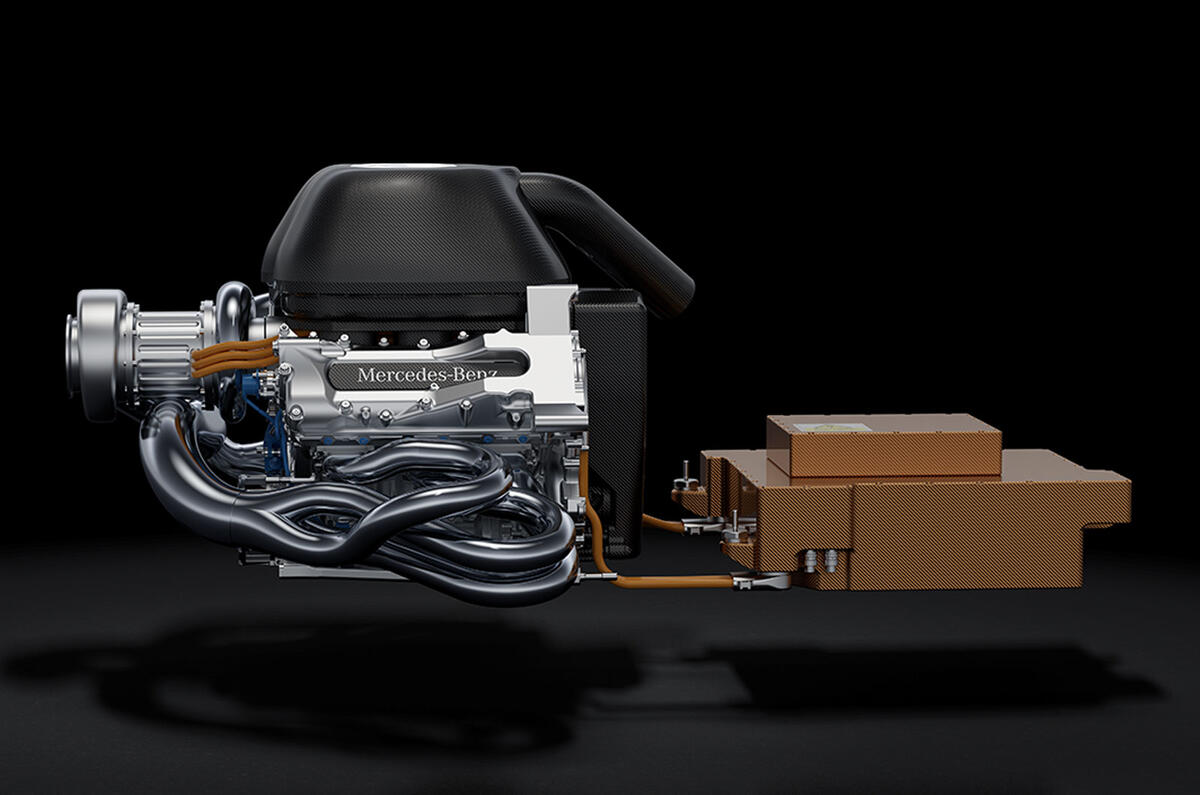

People like Cowell deal in horsepower, but they’re engine people no longer. Today’s term is ‘power units’, mainly because a 2014 F1 car is powered from three sources: a 1.6-litre turbocharged petrol V6, an electric motor-generator that collects braking energy and deploys it to boost acceleration, and another that both collects energy from the V6’s rotating turbocharger and deploys it to keep the turbocharger’s compressor rotating, to cut throttle lag.

Today’s F1 driver has 740-750bhp to deploy, about 160bhp of which is electric. He can use his Energy Recovery System button for roughly 30 seconds per lap, much more than before, and whereas recovered energy last year contributed 0.3-0.4sec to a fast lap, this year it’s three to four seconds. Recovered energy makes a 10 times greater contribution – which is as well because the cars carry only 100kg of fuel, a third less than previously. Such huge changes have introduced many technical hurdles, yet no one complains.

“It’s great to have regulations that chase thermal efficiency,” says Cowell. “What we learn is just so relevant. Our power units have grown 35 per cent more fuel efficient in a year. That’s amazing.”

Join the debate

Add your comment

Split Turbo

sosphisticated

We learn the secrets?