Slide of

Slide of

By even the most cautious definition of what a car actually is, there can be no argument that they have been around since at least the 1880s.

That was a period when television broadcasts were an impractical dream and the idea of dividing the planet into time zones was still new.

Since the world in general has changed so much since then, it stands to reason that cars have too. Here is the story of how the cars of the 21st century differ so dramatically from those designed in the 19th:

Slide of

Slide of

Early days

By modern standards, 19th-century cars were not so much designed as put together in what seemed to be approximately the right order. The first Fiat, the 3.5hp of 1899 (pictured), provides a good example of the then-current trend.

Underneath its chassis was a tiny 679cc engine driving the rear wheels. The occupants, who had minimal weather protection, sat in the vis-à-vis formation, with two in the rear facing forward and two in the front facing backwards.

Slide of

Slide of

Engines in the front

Long before modern tuning techniques had been devised, the best way of coping with a demand for more power was to give a car a bigger engine.

The engine in the Renault which won the inaugural French Grand Prix (replica pictured) measured 13 litres. This seems monstrous nowadays, but it was not at all unusual for 1906.

Slide of

Slide of

Long bonnets

Large engines could not be hidden under the rear of the car as small ones had been. Instead, they had to be moved forwards, where they usually drove the rear wheels but sometimes the fronts.

Long bonnets, or hoods, such as that of the 1934 Packard Eight (pictured), became necessary for the practical reason that they had to cover engines of up to 16 cylinders which nobody in the classic era believed could be placed anywhere other than the front of the car.

Slide of

Slide of

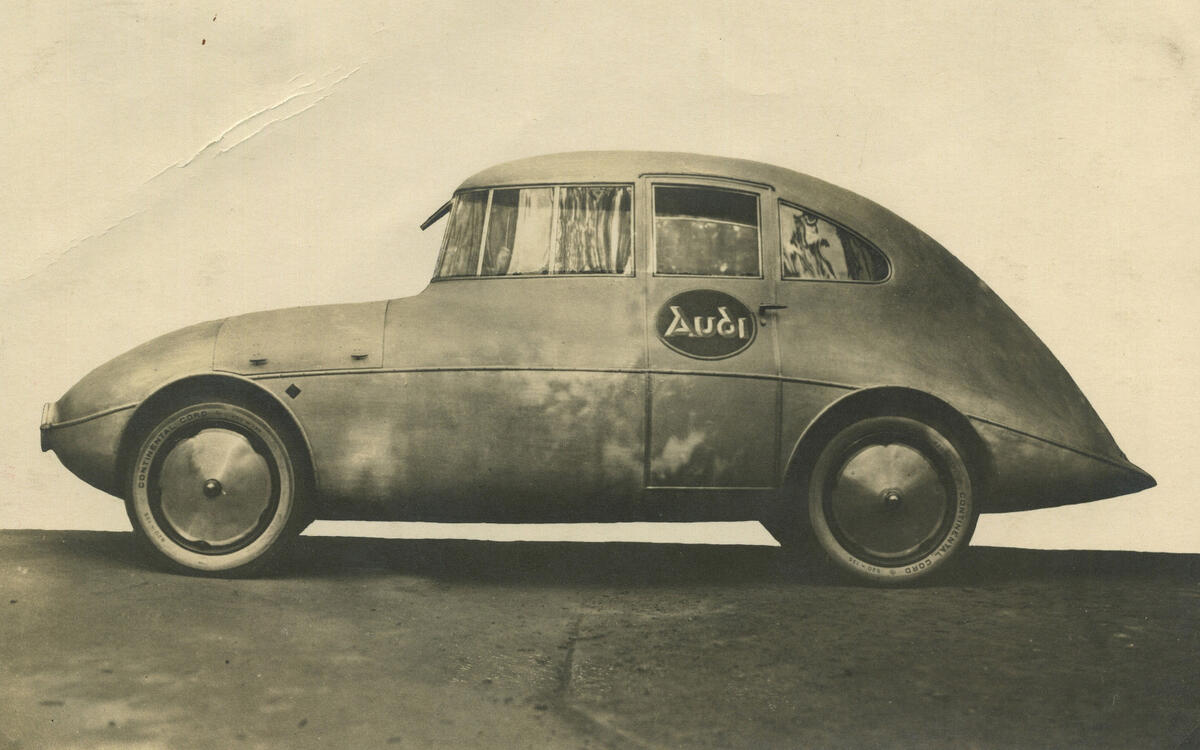

Aerodynamics

Aerodynamics became an important and well-known field of study during World War One, the first major conflict involving air combat.

Pioneers such as Paul Jaray, a former airship designer, built some fascinating streamlined prototypes from the late 1920s – the one pictured being based on an Audi – but they clashed so dramatically with contemporary fashion that there was no hope of them entering production.

Slide of

Slide of

Manufacturers go aerodynamic

It wasn’t until the 1930s, a very important decade in motoring history, that manufacturers began to risk bringing air-cheating cars to market.

One of the first was Chrysler, whose Airflow (also marketed briefly as a DeSoto) went on sale in 1934. Although it was literally the shape of things to come, it was also a commercial flop which persuaded Chrysler to stick to more conservative designs until the 1950s. But the Airflow was enormously influential.

Slide of

Slide of

Integral headlights

The Chrysler Airflow was also unusual in that its headlights were incorporated into the bodywork rather than standing proud of it. This feature, gradually adopted by other manufacturers too, was arguably the single greatest visible change in car design there has ever been.

Peugeot took it a stage further by mounting the headlights of the 402 (pictured) and the later 202 behind its radiator grille. Their very unusual appearance did nothing to harm sales. The 202 was launched in 1938, and you could still buy a new one as late as 1949.

Slide of

Slide of

Unitary construction

The obvious way to build a car for many years was to construct a chassis and then bolt a body on top of it. This method was seriously challenged for the first time during the explosion of radical automotive thinking in the 1930s.

Using technology developed by the Philadelphia-based Budd company, Citroën was first to market with a car whose body also acted as the chassis. Developing the model known as the Traction Avant or Light Fifteen, among other names, sent Citroën into bankruptcy, but the car remained in production from 1934 to 1957.

Slide of

Slide of

Bespoke coachwork

Unitary construction was bad news for independent coachbuilders who had made fortunes building bodies of their own design for everything from Austins to Rolls-Royces. It was quite normal for some manufacturers to provide customers only with a rolling chassis and let them choose a coachbuilder to supply the body.

Many of the resulting cars were quite magnificent, such as the Alfa Romeo 1750 GS with Figoni & Falaschi bodywork pictured. The universal adoption of unitary construction made such machines impossible to build.

Slide of

Slide of

Moving the engine backwards

Except by a few mavericks, the assumption that the front half of a car was the best place for its engine was largely unquestioned until just before the Second World War. The first Volkswagen, retrospectively known as the Beetle, was also the first globally popular car with its engine and gearbox behind the rear axle, leaving plenty of space ahead of it for passengers and luggage.

The Beetle was put into low-volume production in 1938. Post-War, it became the best-selling car in the world without ever deviating dramatically from its original design.

Slide of

Slide of

Rear-engined revolution

Renault followed Volkswagen with its rear-engined 4CV (also known as the 750), which went on sale in 1947. Other small European cars designed on the same principle from the 1950s to the 1970s included Renault’s own Dauphine, 8 and 10, the Fiat 500, the Simca 1000 and the Hillman Imp. In the US, Chevrolet produced the much larger rear-engined Corvair.

The trend has now almost completely disappeared, but Porsche has been using this layout for the 911 (pictured) since 1963 and is showing no sign of abandoning it.

Slide of

Slide of

Front-wheel drive (America)

Europeans rarely think of the US as a front-wheel drive (FWD) nation, but they are wrong. Walter Christie raced FWD cars on both sides of the Atlantic before World War One, and Harry Arminius Miller was successful with Indianapolis racers of the same format in the 1920s.

A very early example of a front-wheel drive American road car was the splendid Cord L-29 (pictured) of 1929. The later Oldsmobile Toronado, introduced in the 1966, had a 7.0-litre V8 engine powering the front wheels only.

Slide of

Slide of

Front-wheel drive (Europe)

The Citroën Traction Avant and almost every car built by DKW were front-wheel drive, but they were unusual for their time. What changed everything was the arrival of the Mini (pictured) in 1959.

In order to maximise interior space, the Mini wasn’t just front-wheel drive. It also had an engine mounted above the gearbox and facing side-to-side rather than front-to-back. Engines in modern FWD cars sit beside their gearboxes, but other than that the Mini layout has become all but universal among mass-market cars.

Slide of

Slide of

Estate cars

Estate cars (also known as station wagons or shooting brakes, among other terms) are usually converted saloons or hatchbacks intended to provide extra luggage space. The earliest are believed to have been Ford Model Ts adapted by independent body builders around 1910 and known as depot hacks.

The concept later spread to Europe and beyond. Estates were very popular for a long time, though customer preference later shifted first to MPVs and then to SUVs.

Slide of

Slide of

Hatchbacks

Hatchbacks are usually defined as cars which are not estates but do have large, top-hinged rear doors, most often (though there are exceptions) containing the rear window.

Renault is widely agreed to have got there first with the 4. Launched in 1961, it was followed four years later by the similar, but larger, 16. Hatchbacks became so popular in Europe that they all but obliterated saloon cars, at least in the small and medium sectors, though saloons remain popular in other markets.

Slide of

Slide of

The return of aerodynamics

After the burst of interest in the 1930s, aerodynamics became a less significant part of vehicle design until the early 70s, when the global fuel crisis made people far more conscious of fuel economy than they had been just a few years before.

Since then, aerodynamic concerns have never gone away, and manufacturers started to advertise their cars' low drag coefficient, such as the Audi 100 (pictured). For nearly half a century, most cars have been streamlined in the interests not only of economy but also of CO2 emissions, noise and, in the case of electric vehicles, range.

Slide of

Slide of

Safety

Automotive safety legislation was introduced in the 1960s and has become more complex and stringent ever since. It affects not only the construction of cars and the equipment fitted to them, but also to a large extent their appearance.

Although the huge rubber bumpers of the 1970s (as seen on the late-model MG Midget pictured, forced by US regulations but also installed in other markets to control costs) are a thing of the past, manufacturers are still limited in how they can style their products - particularly the front end - by safety requirements.

Slide of

Slide of

MPVs

Multi-purpose vehicles, commonly known as MPVs or minivans, are essentially van-like cars with plenty of interior room, anything up to nine seats and usually as many comforts as more conventional models. The 1936 Stout Scarab is regarded as being one of the first, but the Renault Espace (pictured) and Dodge Caravan of 1984 are usually agreed to be the earliest modern MPVs.

MPVs were once very popular, but public interest has since switched to SUVs.

Slide of

Slide of

SUVs

SUVs (sport utility vehicles, sport utes, off-roaders, 4x4s and so on) are tall cars of various sizes designed either to be able to work on tarmac or on rough ground or – as is more commonly the case now – to look as if they can.

A good example of an early SUV would be the original Land Rover, introduced in 1948. Nowadays, however, SUV buyers expect more comfort than that car could offer, so the more luxurious Range Rover, dating from 1970 (pictured), provides a more relevant comparison.

Slide of

Slide of

Crossovers

The astonishing rise of the SUV in the last decade has been due largely to the introduction of crossovers, or lifestyle SUVs as they used to be known. Most of them look as if they can perform well off-road, and they certainly have more ground clearance than the saloons or hatchbacks on which most of them are based, but four-wheel drive features very rarely on the better-selling models.

High seating positions, ease of access for passengers and increased luggage space are what have made these vehicles so popular. Off-road ability no longer has anything to do with it.

Slide of

Slide of

Digital instruments

Several manufacturers, starting with Aston Martin, tried to introduce digital instruments in the 1970s and 80s, but the concept didn’t really get going until the arrival of thin film transistor (TFT) liquid crystal displays (LCDs). Volvo and Audi were early adopters, though other manufacturers have joined in.

TFT LCDs are generally very attractive, and more importantly they are also selectable, so the driver can see the information they most want to, for example prioritising performance, fuel economy or navigation. PICTURE: Audi Virtual Cockpit

Slide of

Slide of

Touchscreens

The rapidly increasing availability of touchscreens on phones or tablets led to customer feedback that they should be included in cars too. They are now very common on everything from city cars upwards, though usually only in the more expensive versions of each model.

The lack of buttons for minor controls was welcomed at first, but since they are easier to use and require less concentration a minor backlash against touchscreens has started. It may be that buttons will soon make a comeback.

Slide of

Slide of

Larger wheels

The earliest cars had very large wheels, but a trend for smaller ones started to develop, to the point where the standard diameter for the classic Mini was just ten inches. That trend has reversed in recent decades – wheel diameters of 20 inches or more are now not uncommon.

Given the chance, customers will very often pay extra for larger wheels because they look better, though they can have a terrible effect on ride quality and often make the wheels easier to damage against curbs. It helps if manufacturers tune their cars’ suspension to the larger wheels in the first place, but this does not always happen.

Slide of

Slide of

Windows

The primary function of a car window, you might think, is to allow people sitting inside to see out. This seems to have become less of a priority in recent years, as pillars have become thicker and glass areas smaller.

Attempts by manufacturers to kick this habit are welcome, but sadly rare.

Slide of

Slide of

The new complexity

Mainstream cars of the 1990s were often criticised for being bland, but a quarter of a century later they are starting to look elegantly unfussy. The styling of today’s cars is far more complex. Designers seem to have got themselves into an arms race where every model has to stand out from its rivals.

If the process continues, cars which come to market in 2035 might be far more intricately designed than they are now. Alternatively, a backlash might lead to a demand for much cleaner styling, and we may wonder what on earth manufacturers were thinking about back in 2019.

Slide of

Slide of

Grilles

An imposing radiator grille was once a defining feature of a car’s design, to the point where you could recognise a Bugatti or a Delage by its grille and nothing else.

By the turn of the century, grilles had all but disappeared. Since then, some manufacturers, notably BMW (BMW X7 pictured) and Lexus, have opted for grilles which are large and distinctive, though not necessarily attractive to all viewers. As with complex design in general, it’s unclear whether this will turn out to be the start of a new trend or a temporary blip. Grilles have a practical purpose since they aid natural cooling of a front-mounted combustion engine; but this is largely not needed in electrically-powered cars.

We look at the key changes made to the car since the very beginning, charting every major change

Advertisement