Sunday 2 November 2025 marked 130 years since the first appearance of ‘a journal published in the interests of the mechanically propelled road carriage’ in Britain.

The Autocar was created in a period that seems alien to modern minds – yet can also be strangely familiar. In celebration, here we revisit the nine issues from our debut year of 1895.

Our first article pondered what this invention would be called. Our incorrect prediction was a handy shortening of ‘automobile carriage’ or ‘automatic carriage’.

Enjoy full access to the complete Autocar archive at the magazineshop.com

Then our treatise: “Every new movement is fostered and encouraged by publicity and the free letting in upon it of the light of public opinion. The power of the press of this country as an educator and a moulder of sentiment is unparalleled.”

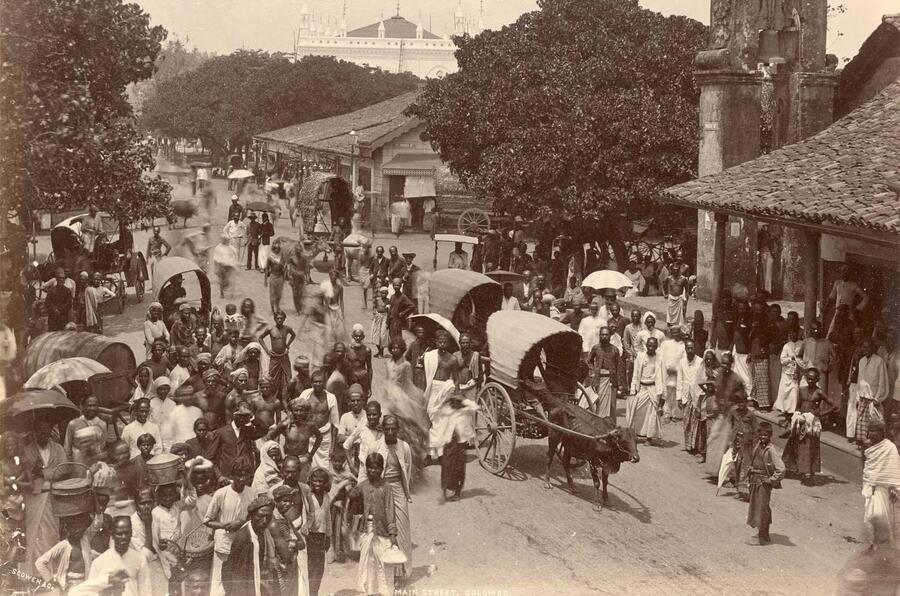

Surely a close second was the opportunity to see a car in action, afforded to the public for the first time at Tunbridge Wells in Kent. Two well-to-do gentlemen, Evelyn Ellis and David Salomons, lapped the agricultural showground at up to 15mph before 5000 people, in their Panhard and Peugeot cars – the first two ever imported.

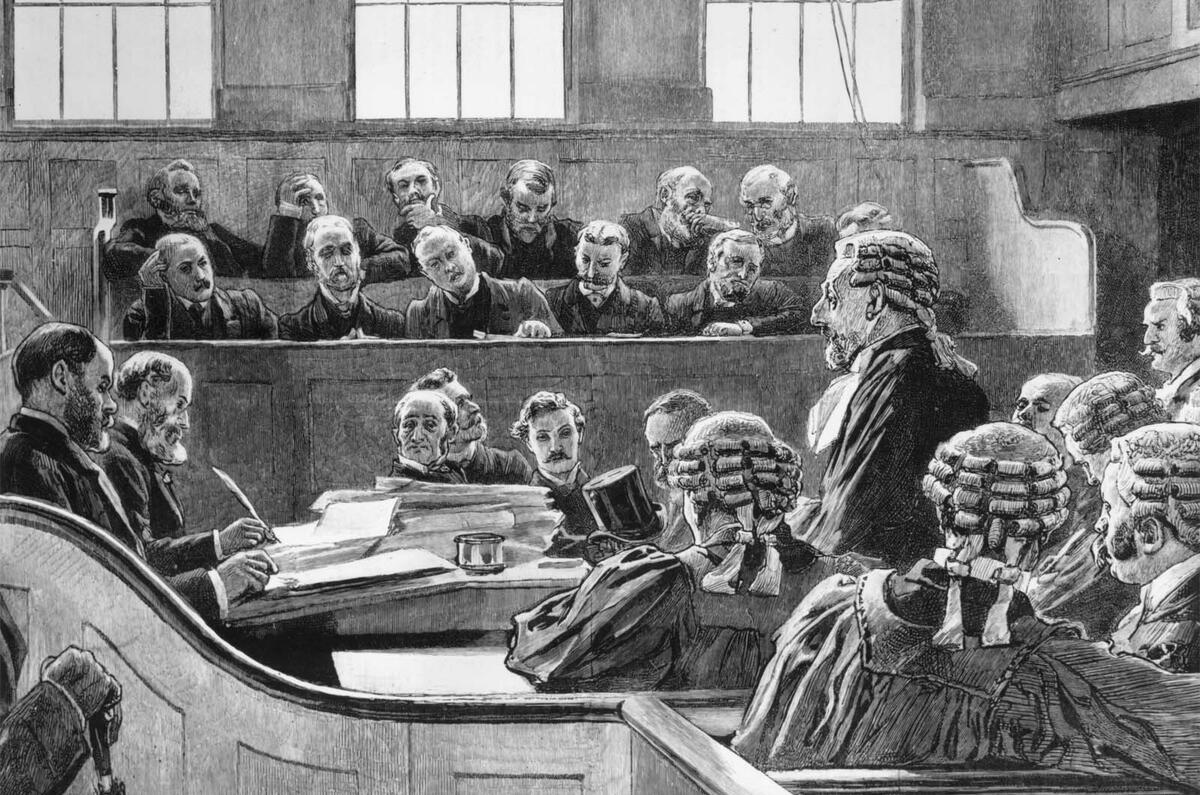

We also discussed the tricky legal situation faced by pioneers (motorised traffic came under the Highways and Locomotives Act 1878) – and the problem reared its ugly head just a week later, as one JH Knight of Farnham in Surrey was fined 2s 6d for driving without a licence from the county council.

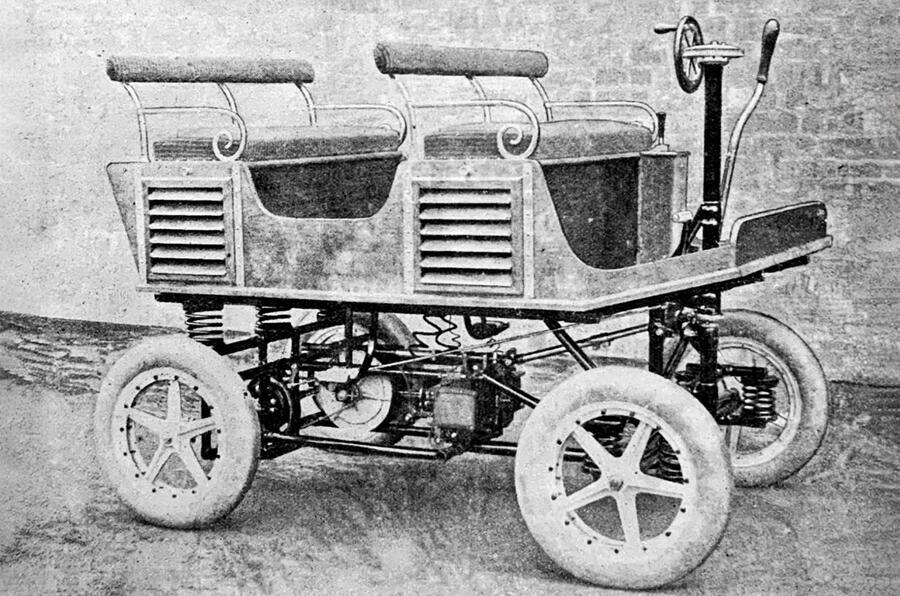

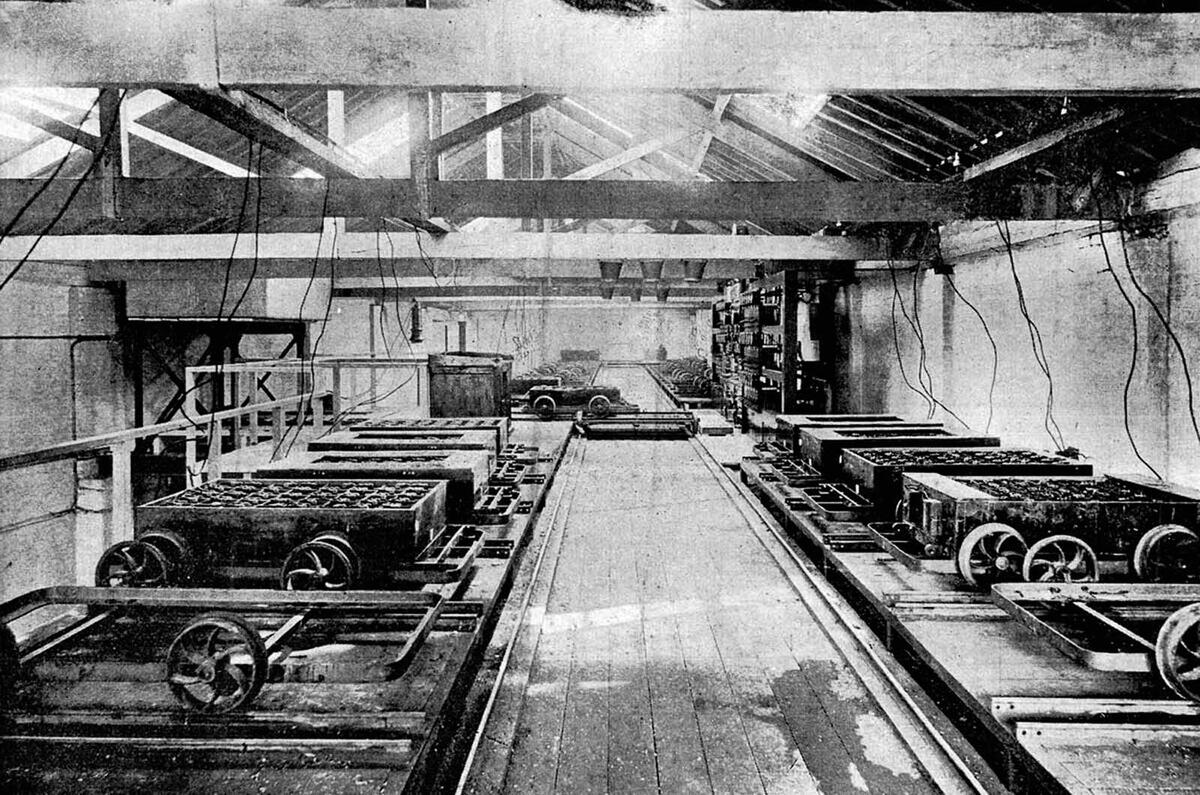

After an American petrol car in issue one, we detailed an electric car from Coventry cycle maker Blumfield & Garrard in issue two. With an 80-mile range and a top speed of 10mph, the “strange beastie” impressed us greatly on a ride around the workshop.

A week later, we learned from one Harry Lawson that a firm was being formed for British car making on “a very large scale”, using patents licensed from Germany’s Daimler – the inventor of the car in 1885 – and American newcomer Edward Pennington.

We were excited about his engine, since by using a ‘water jacket’ it “produces both heat and cold, and in such proportion that the temperature of the cylinder is never greater than that of an ordinary steam engine, and requires a minimum quantity of water”. It soon transpired that Lawson and Pennington were conmen.

On 12 November, the world’s first automobile club was founded, with “the best men in France” among its members. We said: “While intended for the convenience of members, and especially of provincial autocar users who may wish to be in touch with Paris, [the ACF] will do everything in its power to advance the interests of the new industry.”

Join the debate

Add your comment

An interesting article that highlights the progress made by the automobile industry and the lost art of great writing.