The timing of my first few yards in AC’s ‘new’ Cobra MkII 347 is spectacularly bad. Gingerly making my way from its temporary base above Brooklands Museum’s historic Finishing Straight, the heavens open with truly biblical fervour.

Any thoughts of a road trip in this factory continuation car that even hints at the Cobra 427’s transamerica thrash in the 1976 film The Gumball Rally are washed away as quickly as some of the loose rubble on Brooklands’ track.

If nothing else, our slightly shorter schlep will now include some of Gumball’s filmic grit as we take on the rain-swept roads of southern England, picking up destinations that have particular relevance to this 2024 Cobra’s heritage.

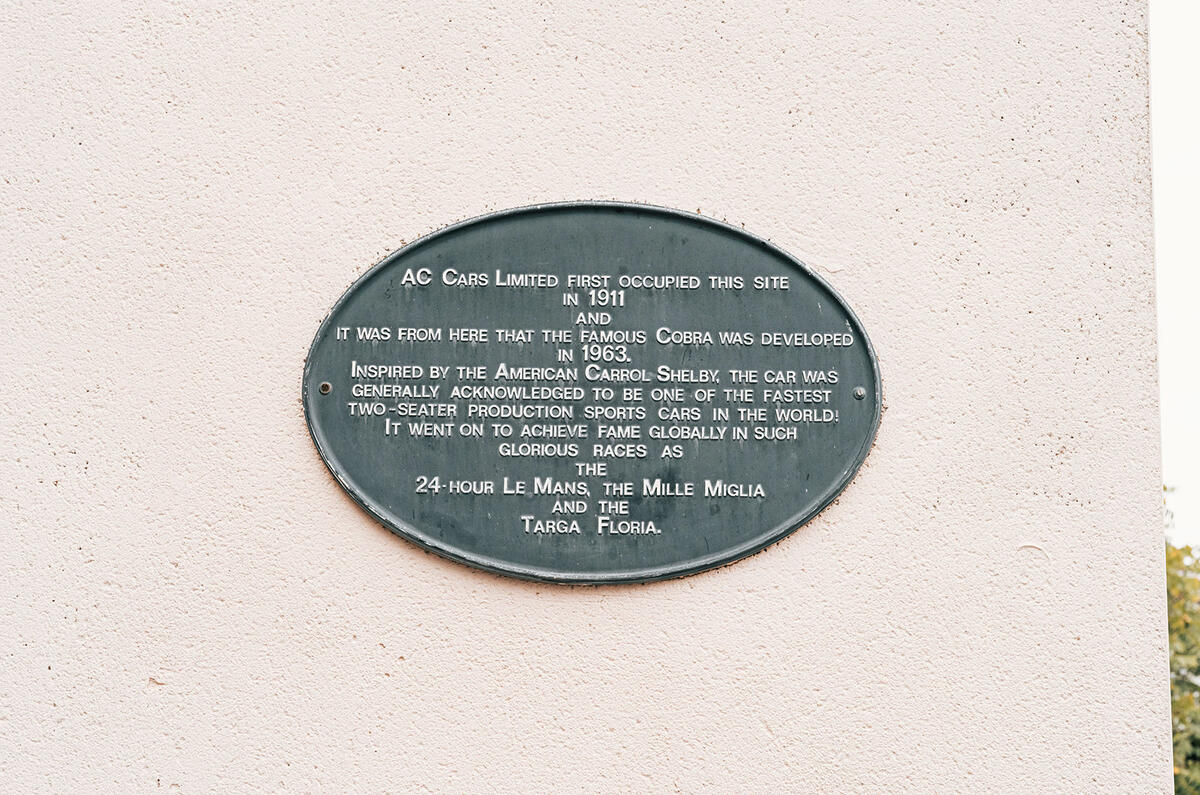

AC Cars, as you will have seen from Matt Prior’s prototype drive of the new Cobra GT Roadster, is now bringing the marque full pelt into the 21st century.

But the car I’m driving is the Roadster’s genesis, being one of four final MkII Cobras the factory will make and ending a somewhat erratic production run, which started more than 62 years ago in February 1962.

Of course, this last-of-the-line MkII is not completely faithful to its 1960s forebear, with each car needing to comply with current Individual Vehicle Approval regs.

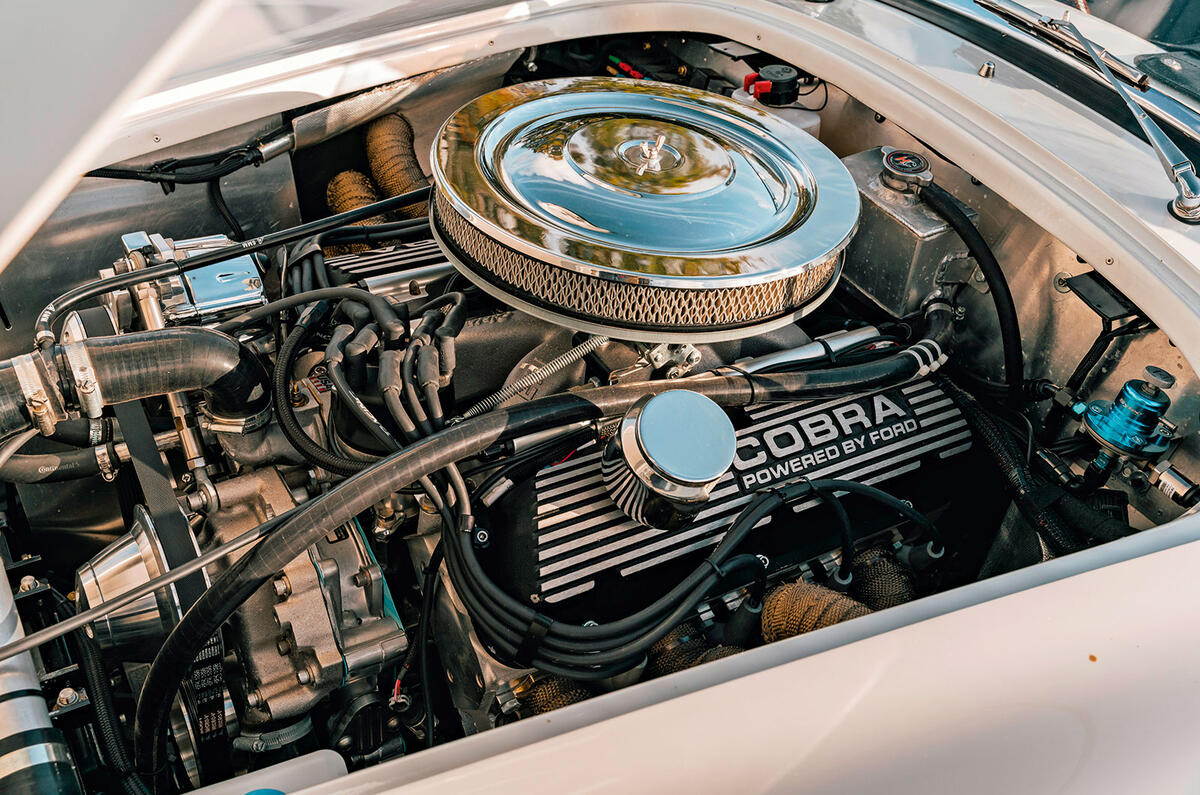

The upside is that the MkII’s power output is up by 50% to 400bhp, thanks to the installation of a bespoke, 347cu in (that’s 5.7 litres) Ford V8, the design of which is based on the original car’s ‘small-block’ 289cu in, or 4.7-litre, unit.

Still with an iron block and aluminium heads, the engine is built to AC’s own specification by Prestige Performance in North Carolina and, as you would expect, swaps the in-period four-barrel Autolite carb for modern Holley fuel injection.

Mated to this is a five-speed Tremec TKX gearbox, which, as we will see, is thoroughly in keeping with the Cobra’s character. It delivers drive to the rear wheels via a Quaife limited-slip differential.

Other than these not insignificant changes, the MkII is the genuine article.

Its body is identical to that of the original model (save for being made from composite materials rather than aluminium) and, to my eyes at least, is the sweet spot of the Cobra dynasty, looking more like the AC Ace on which it was based rather than the MkIII with its Carlos Fandango tyres and steroidal arch extensions.

Add your comment