The greatest irony about supercars has always been the fact that, despite being designed for the pleasure of driving, they tend to do minimal miles.

Which is why Simon George’s Lamborghini Murciélago stands as a glorious – and very orange – riposte to all those pampered queens in their air-conditioned garages. Not only has it already covered 258,000 miles, surviving a near-death experience along the way, but it’s also still racking up miles quicker than a sales rep’s BMW 320d.

George’s route to Lamborghini ownership was an unorthodox one. In the late 1990s, he was working as a British Gas engineer while building a modest buy-to-let property portfolio. In 2004, he remortgaged this to raise £30,000 as a deposit for a brand-new Murciélago. “I’ve always lived life on the edge,” he says. “The finance payments were about three grand a month – the car was £180,000 – and I only had enough money put away for about eight months, so I knew the car would have to earn its keep.”

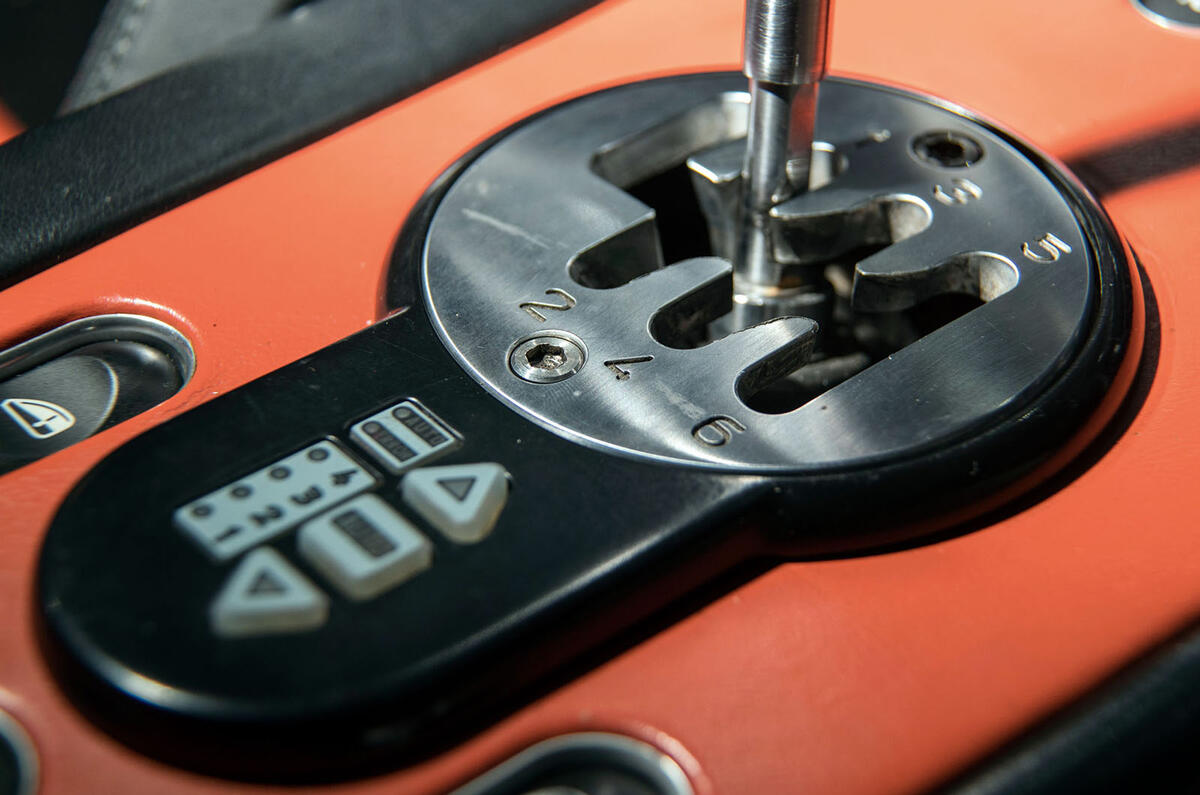

So he started working for a supercar experience company, taking his ARDS (Association of Racing Drivers Schools) licence so he could work as an instructor and sit next to people who were paying to thrash his pride and joy. After a couple of years of this, he and business partner Andy Cummings branched out on their own and set up 6th Gear Experience – with the Murciélago becoming the pride of its corporate fleet.

For the next five years, the Lamborghini worked pretty much non-stop, doing up to 90 events a year for 6th Gear, with dozens of different drivers at each, and covering 600 miles a week travelling up and down the country on top. With fuel economy “never better than 16mpg”, clutches lasting no more than 30,000 miles and a new set of tyres more than once a month, costs soon began to mount.

But nothing prepared George for the financial pain that was to come. In late 2012, a customer lost control at a driving day and crashed the Murciélago into a tree head-on at about 40mph. “Nobody was injured, thankfully,” George says, “but the car was a proper mess. The roof was bent. The chassis was warped.”

George says he knew he was going to repair the car almost before the dust had settled – “it was one of those heart-over-head things” – but it took four years and around £90,000 to get it back on the road. That included straightening the chassis with a special supercar-grade jig and some very expensive parts. (The headlights were £6000 each.) The total could have been even higher but George got special labour rates from Lamborghini Manchester, which sold the car originally, and some of 6th Gear’s mechanics volunteered unpaid overtime to get the car repaired. Now retired from frontline duties, ‘SG54 LAM’ has become George’s daily driver again, racking up the miles on his commute from Sheffield to 6th Gear’s HQ in Sutton Coldfield. Bigger trips to Scotland and the Lamborghini factory at Sant’Agata are also planned.

Join the debate

Add your comment

lots of words...

... not many relevant to a road car. dog boxes need wider gears to transmit the same amount of torque, and those clutchless shifts need to be done carefully if you want it to last a while. the sort of "absolutely as fast as possible" driving you describe isn't how anyone should be driving on the road. Spend all your time left foot braking an auto, then drive a manual; at some point you're going to stomp the clutch down and think the brakes have failed, probably during an emergency. semi-auto increases fuel consumption, even with regular clutches, as the hydraulics use power. Reliability and repair bills, should I mention those? dsg mechatronics, etc. Why do you see a manual shift as being so bad you equate it to manual timing adjustment? it's really not the same at all

Manual transmisions.

Dancing around on the pedals is undoubtedly and undeniably a major skill. So is riding a unicycle. Did you know there are people who ride unicycles cross country?

Fortunately paddle shifting now lets you concentrate on managing and fully utilizing the grip generated by the tires, in braking, acceleration,and cornering, which is kind of the point of the whole "go fast in the car" exercise. With no nanny controls keeping you out of trouble, driving a car on the ragged edge of adhesion using the steering wheel and the brake and accelerator pedals is pretty challenging. You can't go as fast if you're allowing enough margin to unsettle the car with downshifitng, no matter how well done.

In fact paddle shifting allows and encourages left foot braking, an arguably more sophisticated skill than stirring the stick on a manual, and one that absolutely leads to going faster if done right. Many most racing drivers for 60 years now have learned in go-karts. Left foot braking, no dancing on the pedals, manage that grip. Short, twitchy, "Oh my we're backwards again".

If you enjoy dancing on the pedals good on you. I challenge you to find a road race driver that doesn't prefer a paddle shifter where possible. Dancing on the pedals is still a necessary evil sometimes, but to be avoided if possible. You have better things to do.

And you do realize that even with a full manual transmission, if it's a dog box, as all serious transmissions are, you're not using the clutch after you start anyway. And you're right back to being able to left foot brake if the footbox configuration allows or is adapted. In any case, just like every motorcycle for a very long time, "we don't need no stinking synchros". A very firm and deliberate and definite touch is required, nothing tentative or casual, but no "baulk" rings, another word for synchros that accurately describes one of their major functions. To prevent the shift. No synchros, no double clutch dancing on the pedals.

258K, New clocks needed or clocking forward?